Endocrine Active Chemicals/Wastewater Treatment Plant

Minnesota PROJECTS

ABOUT THE MINNESOTA

WSC

USGS IN YOUR STATE

USGS Water Science Centers are located in each state.

|

BACKGROUND

Streams receiving wastewater-treatment plant (WWTP) effluent have been documented to contain chemicals used in private homes, industry, and agriculture. A subset of these chemicals, endocrine active chemicals (EACs) (Ahel and others, 1994a, b; Desbrow and others, 1998; Ternes, 1998; Kolpin and others, 2002) and pharmaceuticals (Lajeunesse and others, 2008; Schultz and Furlong, 2008) have been identified in WWTP effluents and in surface waters in Minnesota (Barber and others, 2000, 2007; Lee and others, 2004; Lee, Schoenfuss, and others, 2008; Lee, Yaeger, and others, 2008; Martinovic and others, 2008; Writer and others, 2010). EACs include natural and synthetic chemicals that mimic or block the function of natural hormone mediated systems in animals, including fish (Kime, 1998; National Research Council, 1999) and invertebrates (Gagnaire and others, 2009). Although no single list of EACs exists, laboratory studies have confirmed that certain classes of chemicals including natural and synthetic hormones, pesticides, trace metals, alkylphenols, alkylphenol ethoxylates, plastic components, phthalates, and phytoestrogens affect the endocrine systems of fish through biochemical, structural, and behavioral disruption (Jobling and Sumpter, 1993; Jobling and others, 1996; Ankley and others, 1998; Kime, 1998; Miles-Richardson and others, 1999; Bistodeau and others, 2006; Barber and others, 2007; Schoenfuss and others, 2008). The presence of pharmaceuticals in surface waters can alter normal body functions of aquatic species, including invertebrate reproduction (Nentwig, 2007) and fish behavior (Painter and others, 2010).

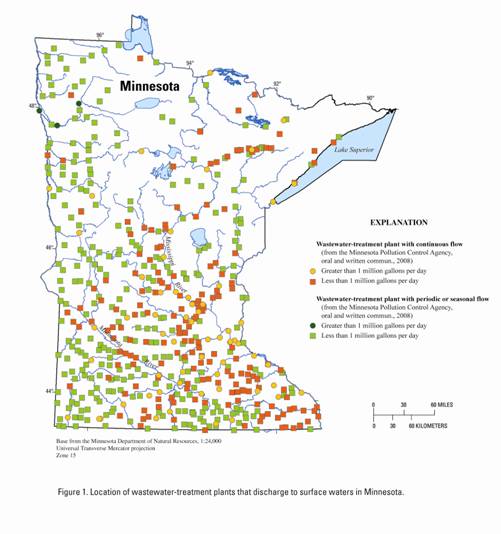

More than 500 WWTPs throughout Minnesota discharge treated wastewater to surface water (fig. 1). Approximately 75 percent of the WWTPs release effluent periodically (generally biannually during the spring and fall) with design flows less than 0.04 cubic meter per second (m3/s; 1 million gallons per day (Mgal/d)). Approximately 60 WWTPs discharge continuously to receiving streams with average design flows greater than 0.04 m3/s (Lee and others, 2010).

Results from several investigations (Barber and others, 2000, 2007; Lee, Schoenfuss, and others, 2008; Lee, Yaeger, and others, 2008; Martinovic and others, 2008; Lee and others, 2010) indicate that concentrations of EACs in Minnesota WWTP effluent and receiving streams greatly vary. For example, nonylphenol was detected in effluent from 9 of 11 previously studied WWTPs at concentrations ranging from less than the detection level to 18.2 micrograms per liter (µg/L) among all samples (Lee and others, 2010).

The variability in chemical occurrence and concentrations in WWTP effluent is dependent upon the influent type and processing techniques of each WWTP (Richardson and Bowron, 1985; Stumpf and others, 1996; Ternes, 1998). Huang and Sedlak (2001) and Drewes and others (2005) determined that tertiary wastewater treatment resulted in a 70-percent reduction of EACs, and advanced treatment with reverse osmosis resulted in a 96-percent reduction of EACs. Drewes and others (2005) determined that although sewage treatment reduced the overall estrogenicity, effluents still had sufficient estrogenicity to elicit a response from a human breast cancer cell assay.

Indicators of endocrine disruption including elevated concentrations of vitellogenin in male fish (an egg yolk protein present in female fish but generally absent in male fish) and intersex occurrence (oocytes present in testes tissue) have been observed downstream from wastewater discharges (Folmar and others, 1996, 2001; Lee and others, 2000, 2010; Goodbred and others, 1997; Lee and Blazer, 2005; Lee, Schoenfuss, and others, 2008; Lee, Yaeger, and others, 2008).

Although WWTP effluent has been identified as a contributor of EACs to the aquatic environment (Desbrow and others, 1998; Ternes and others, 1999; Johnson and Sumpter, 2001; Vajda and others, 2008), EACs also have been detected in streams and lakes with no obvious WWTP effluent discharges indicating that other sources of contamination are contributing EACs (Lee and others, 2004, 2010; Lee, Schoenfuss, and others, 2008; Writer and others, 2010). EACs and pharmaceuticals can enter aquatic systems through a variety of pathways in addition to WWTP effluent including industrial effluent discharge, runoff from agricultural and urban land surfaces, land application of human and animal waste and subsequent movement to groundwater or surface water, and septic system discharge.

Although research and monitoring efforts have identified EACs and pharmaceuticals in WWTP effluent and receiving streams in Minnesota, the number of WWTPs sampled among the various studies represent a small fraction (less than 5 percent) of the WWTPs in Minnesota. In addition, little is known about EACs in bed sediment, which may serve as a reservoir of these chemicals in aquatic environments.

The chemicals analyzed in this study were selected because they are indicators of human- and animal-waste sources to the environment and can affect aquatic organisms, although many of the chemicals also have natural sources (Barnes and others, 2008). The presence of naturally occurring compounds alone may not indicate a human- or animal-waste source, and some of the naturally occurring chemicals are incorporated in commercial products. Details of the potential natural sources are beyond the scope of this report, but may come from microorganisms, plant or animal sources, and may include by-products of combustion or other natural processes (Barnes and others, 2008).

|